Increasing your running cadence is one of the most effective and easiest ways to clear up nagging aches and pains.

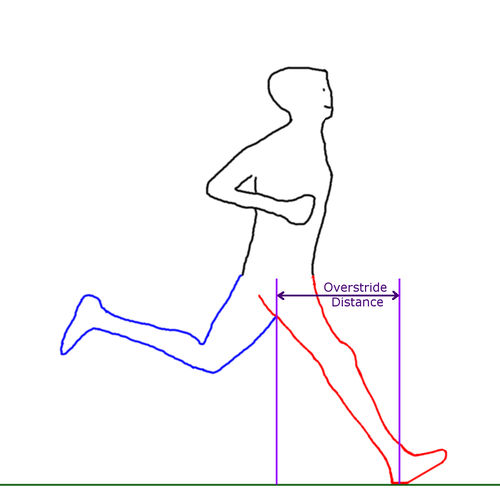

If you’re a runner – be it new to the sport or a seasoned pro – and you’re dealing with some nagging pains or aches, one of the easiest ways to clear that up is by determining and then increasing your running cadence by 5 to 10%. That’s because running cadence is inversely related to your stride length with a lower cadence associated with overstriding.

Overstriding has been linked to higher injury rates in runners (1-5), one of numerous reasons why injury rates in the running community remain very high an estimated 56% of recreational runners and as high as 90% of marathoners in training suffering a running-related injury (6).

You may be wondering “well, that’s great and all but how do I easily calculate running cadence and what am I aiming for?”

You’re in the right spot. Here’s how.

How to calculate running cadence

While running at a moderate pace on a flat surface – a track or treadmill for example – set a timer for one minute. Choose either your right or left foot and over the course of that minute count every time that foot hits the ground.

Take that number and multiply it by two. That’s your running cadence or stride rate, with a unit of steps per minute (spm). Pretty simple right?

The goal is to take that running cadence number and increase it by 5-10% which has consistently been shown to decrease overall impact forces and muscle loading while increasing the efficiency of your running gait (1-5).

There’s no specific spm target number that we’re trying to achieve. There’s long been a common and pervasive myth that the ideal running cadence is exactly 180 spm. That’s simply not true and that misinformation was spread based on a misunderstanding of the original research by running coach Jack Daniels which – as happens far too often – was taken at face value, repeated, and over time became taken as fact.

Each and every runner has unique characteristics and variables which will affect their running cadence. It’s never one size fits all, with more and more research showing that to be true (6-9).

Further, I don’t suggest simply switching over to that higher running cadence immediately. Like anything else, it has to be a gradual transition to ensure safety and carryover. To that point, I’ll share an easy, safe, step by step running cadence process in next week’s blog.

Thanks for reading and remember health and performance are two sides of the same coin.

Sources:

1. Napier C, Cochrane CK, Taunton JE, Hunt MA. Gait modifications to change lower extremity gait biomechanics in runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(21):1382-1388. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094393.

2. Barton CJ, Bonanno DR, Carr J, et al. Running retraining to treat lower limb injuries: a mixed-methods study of current evidence synthesised with expert opinion. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(9):513-526. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095278.

3. Willy RW, Buchenic L, Rogacki K, Ackerman J, Schmidt A, Willson JD. In-field gait retraining and mobile monitoring to address running biomechanics associated with tibial stress fracture. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(2):197-205. doi:10.1111/sms.12413.

4. Heiderscheit BC, Chumanov ES, Michalski MP, Wille CM, Ryan MB. Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(2):296-302. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ebedf4.

5. Adams D, Pozzi F, Willy RW, Carrol A, Zeni J. ALTERING CADENCE OR VERTICAL OSCILLATION DURING RUNNING: EFFECTS ON RUNNING RELATED INJURY FACTORS. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(4):633-642. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30140556.

6. van Gent RN, Siem D, van Middelkoop M, van Os AG, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Koes BW. Incidence and determinants of lower extremity running injuries in long distance runners: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(8):469-80; discussion 480. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.033548.

7. Burns GT, Zendler JM, Zernicke RF. Step frequency patterns of elite ultramarathon runners during a 100-km road race. J Appl Physiol. 2019;126(2):462-468. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00374.2018.

8. Cavanagh PR, Kram R. Stride length in distance running: velocity, body dimensions, and added mass effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989;21(4):467-479. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2674599.

9. Salo AIT, Bezodis IN, Batterham AM, Kerwin DG. Elite sprinting: are athletes individually step-frequency or step-length reliant? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(6):1055-1062. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318201f6f8.