The most effective way to prevent ankle sprains is a combination of neuromuscular and strength training. Part one dives into neuromuscular training.

Ankle sprains can be debilitating, are far too common, and account for the most time lost of any injury (1–6). Two facts I’m acutely aware of as I have a long and painful history with ankle sprains myself and as I became a therapist on the frontlines of treating ankle sprains, it only reinforced the toll they take on athletes.

A common solution, and one I used for myself for a long time, was using ankle braces as a protective measure. However, although bracing can be effective as I wrote about here, it’s a band-aid measure that doesn’t address the root cause. I never want to depend on external supports.

Going through the research, two types of training – particularly when done in combination – have proven to be the most effective at reducing ankle sprains: neuromuscular and strength training (1,2,7–14).

By upwards of 79% in some studies (1,7,9,11,14)!

Part one of this blog delves into neuromuscular training and part two into strength training, with specific incremental routines to address each. Let’s start with an explanation of the neuromuscular system.

The neuromuscular system

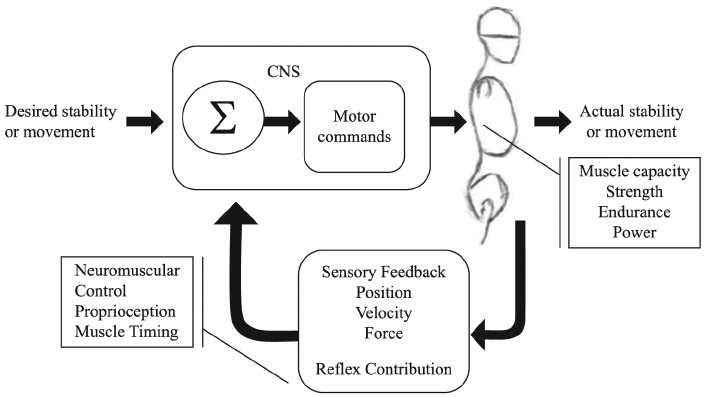

The neuromuscular system is the connection between your nerves and the muscles. If the muscles are the machinery then the nerves are the wiring. Your brain receives information, processes it, and then responds by sending out specific nerve signals to specific muscles to enhance stability and movement. It’s all done extremely quickly and subconsciously.

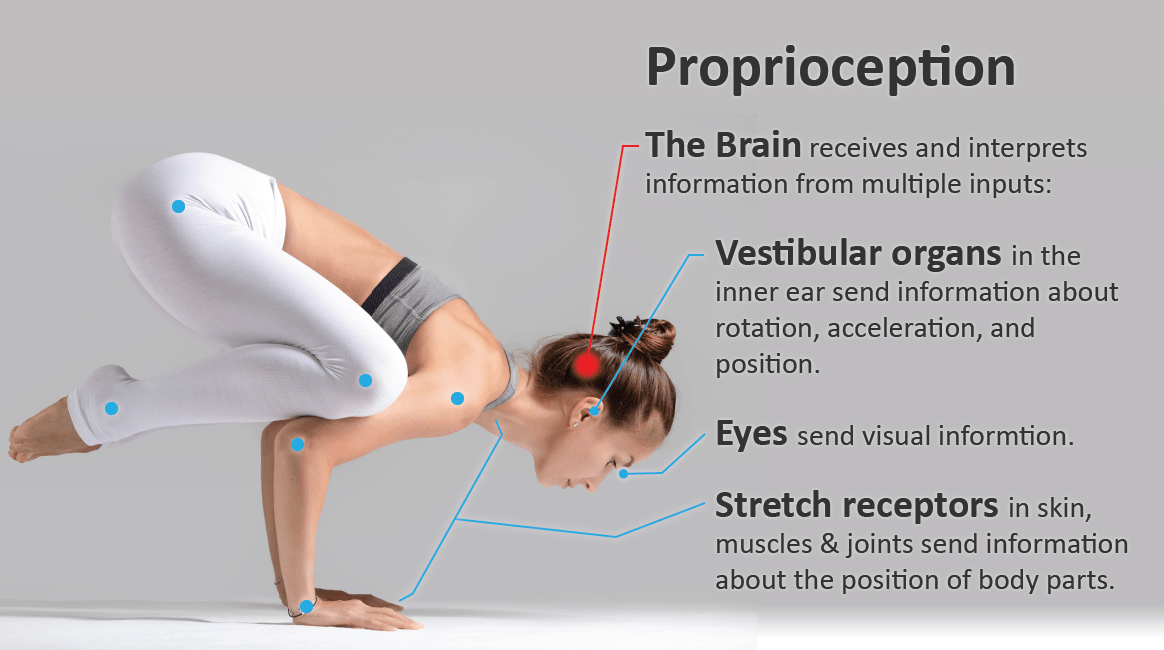

There are three major systems – vision, vestibular, and proprioception – that underlie the neuromuscular system.

Vision speaks for itself so I won’t go into depth on that. It’s often used to compensate for deficits in the other two systems so modulating it is one of the key ways to make this training more challenging and effective.

The first part of this post will be explaining the role of the vestibular and proprioceptive systems as they relate to ankle sprains and then we’ll get into targeted training that addresses vestibular and proprioceptive deficits to reduce your risk of ankle sprains.

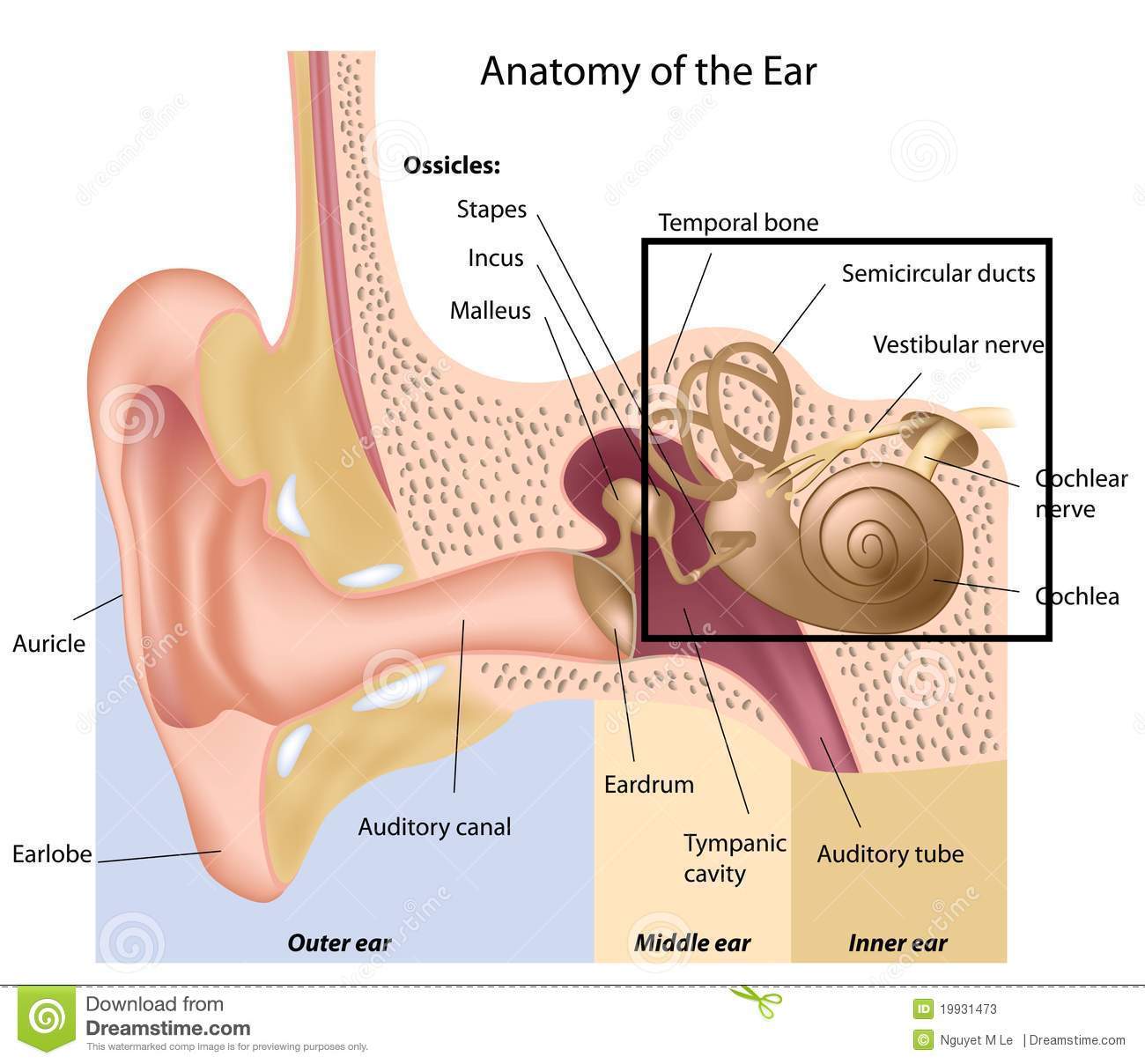

The Vestibular system

The vestibular system is an unconscious sensory system in your inner ear that is intricately linked to balance. Every time you move your head, whether it’s side to side, up and down, or any other head motion, the vestibular system is sending feedback to your brain regarding motion, equilibrium, and spatial orientation.

This “vestibular apparatus” consists of the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals – all housed in your inner ear. Here’s the basic anatomy:

This system provides critical information to your brain and helps it decide which adjustments to make during movement. Imagine you’re driving the lane in basketball or weaving through a tight space in football – as you move your head around to scan the surroundings and get your bearings, there’s constant feedback from the vestibular system about your body’s movement, posture, and overall stability.

The proprioceptive system

The proprioceptive system is an unconscious sensory feedback system that informs the brain about joint position and where your body parts are in space. It’s often referred to as the “sixth sense”. Based on this feedback, the brain activates muscles and makes micro-adjustments.

An easy way to understand proprioception is to imagine if you didn’t have it – try this: close your eyes, and move your hands and fingers around. If it wasn’t for the proprioception system, you would have no idea what your hands and fingers were doing!

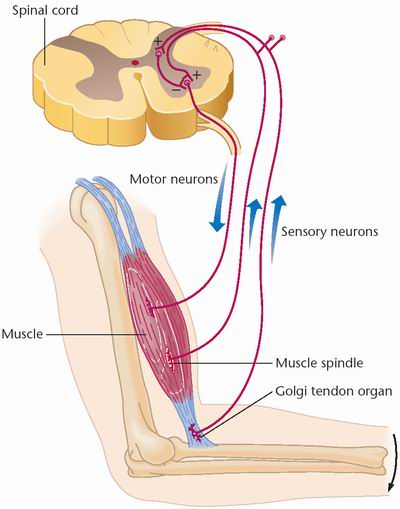

The system relies on receptors in the muscles that monitor length, tension, pressure, and painful stimuli. Here’s a basic anatomical overview:

When your ankle starts to roll inwards, these receptors alert your brain that it’s about to happen. When an ankle sprain does occur, these receptors get stretched out, impaired, and reaction times decrease– leading to a higher risk of future ankle sprains, increased proprioceptive deficits, and so on. It’s a vicious cycle. Therefore, it’s critical that we train this system.

How to train these two systems

Now let’s take that information and apply it practically. There’s two progressions you want to implement to challenge your neuromuscular system in two distinct ways:

1 – Balance training

Once you can complete step one comfortably for a minute on each foot, graduate to the next step. That step now becomes your baseline where you will start the next day.

2 – Active control

Complete on each foot for one minute and, like the girl in the video, you can start out by looking down at your feet. Once you can do that comfortably for the entire minute, move up to the next step during your next sessions. The progressions is as follows:

-

Complete it while looking straight ahead

-

While turning your head side to side

-

While nodding your head up and down

-

With eyes closed

-

If you’re really feeling frisky, eyes closed with head turns and then head nods

Whichever step you’re on becomes your starting point for the next session. The key here is control on jumping and landing, not speed.

The final take

Think of your neuromuscular system – with major inputs from your vision, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems – as the managers. They’re responsible for recognizing a problem – in this case impaired stability or high risk position potentially leading to an ankle sprain – before it happens or while it’s happening and then activating the appropriate safeguards. These safeguards are specific muscles and we’ll get into the specific strength training in part two next week.

Until then, begin implementing these neuromuscular progressions into your daily training. I bet you’ll also see an improvement in your athletic performance and confidence because you’re unleashing the systems responsible for movement and stability.

Thanks for reading and always remember: health and performance are two sides of the same coin.

Sources

1. Doherty C, Bleakley C, Delahunt E, Holden S. Treatment and prevention of acute and recurrent ankle sprain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(2):113-125. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096178.

2. Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(15):956. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098106.

3. Fong DT-P, Hong Y, Chan L-K, Yung PS-H, Chan K-M. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37(1):73-94. doi:10.2165/00007256-200737010-00006.

4. Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(13):2279-2284. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01537.

5. Roos KG, Kerr ZY, Mauntel TC, Djoko A, Dompier TP, Wikstrom EA. The Epidemiology of Lateral Ligament Complex Ankle Sprains in National Collegiate Athletic Association Sports. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):201-209. doi:10.1177/0363546516660980.

6. Dizon JMR, Reyes JJB. A systematic review on the effectiveness of external ankle supports in the prevention of inversion ankle sprains among elite and recreational players. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(3):309-317. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2009.05.002.

7. Taylor JB, Ford KR, Nguyen A-D, Terry LN, Hegedus EJ. Prevention of Lower Extremity Injuries in Basketball: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Health. 7(5):392-398. doi:10.1177/1941738115593441.

8. Owoeye OBA, Palacios-Derflingher LM, Emery CA. Prevention of Ankle Sprain Injuries in Youth Soccer and Basketball: Effectiveness of a Neuromuscular Training Program and Examining Risk Factors. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28(4):325-331. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000462.

9. Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(3):238-244. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.005.

10. Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer K. An evidence-based approach to hamstring strain injury: a systematic review of the literature. Sports Health. 2009;1(2):154-164. doi:10.1177/1941738108324962.

11. Hübscher M, Zech A, Pfeifer K, Hänsel F, Vogt L, Banzer W. Neuromuscular training for sports injury prevention: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(3):413-421. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b88d37.

12. de Vasconcelos GS, Cini A, Sbruzzi G, Lima CS. Effects of proprioceptive training on the incidence of ankle sprain in athletes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(12):1581-1590. doi:10.1177/0269215518788683.

13. McCriskin BJ, Cameron KL, Orr JD, Waterman BR. Management and prevention of acute and chronic lateral ankle instability in athletic patient populations. World J Orthop. 2015;6(2):161-171. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.161.

14. Verhagen EALM, Bay K. Optimising ankle sprain prevention: a critical review and practical appraisal of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(15):1082-1088. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.076406.