Due to multiple knee injuries, Harry Giles has gone from being the top rated high school player in his class and sure-fire top end lottery pick to potentially a late first round pick in the upcoming NBA draft. His level of talent and injury history begs the question: Is he worth taking a gamble on?

To explore that, let’s start with his actual injuries.

The Injuries

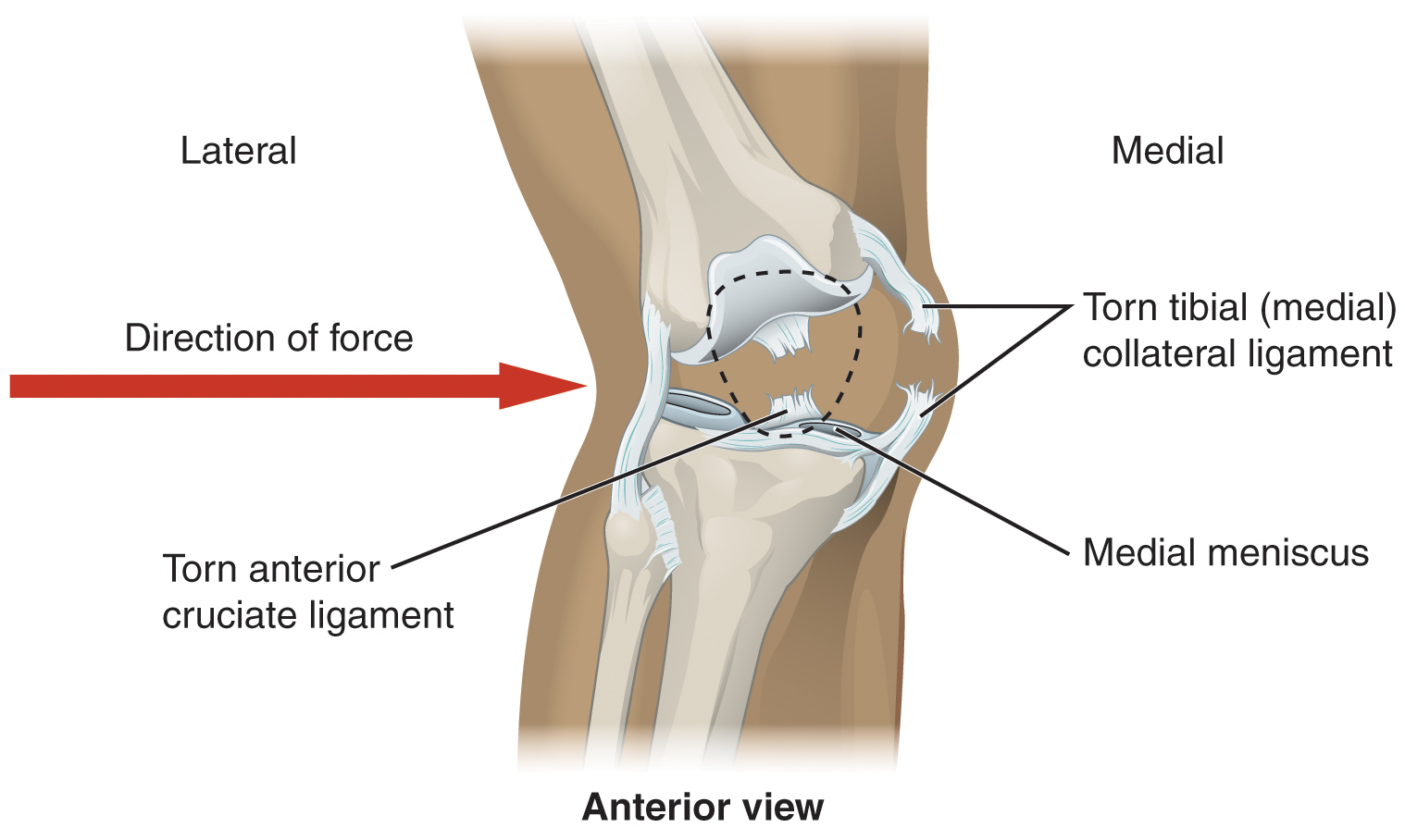

Back in June 2013 at the FIBA Americas U16 Championship, Giles suffered what is often medically referred to as the “unhappy triad” – a tear of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and meniscus.

This most commonly occurs when the knee is struck on the lateral aspect – the outside – while the foot is planted firmly onto the ground. From my understanding, this is what happened to Giles.

This type of injury is considered a contact injury and it’s important to note that distinction for the risk/reward analysis – more on that later.

The force from the contact, if significant enough, can create a valgus – think: inward – and/or rotary force that tears each of the ACL, MCL, and meniscus. An illustration:

After surgery and rehab, Harry came back with a vengeance in 2014 into 2015, killing it at the Nike EYBL circuits and the U17 and U19 FIBA World Championships.

However, during the first game of his high school season, he partially tore his right ACL – a tear that was significant enough to require surgery.

Like his first injury, this was also a contact injury – again, take note for later – with an opponent hitting his knee and driving it inwards. However, the overall extent was not close to that of the left knee injury as only his ACL was impacted.

After sitting out his senior year while recovering and rehabbing, Harry proceeded to take his talents to Durham, Coach K, and the Blue Devils.

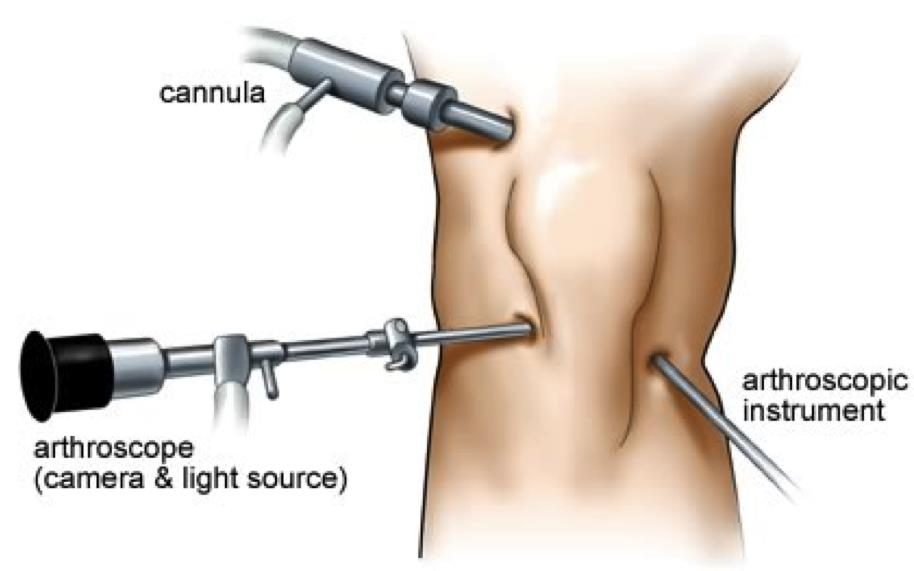

However, before the season could begin, he underwent another procedure on his left knee – an arthroscopy – on October 3rd, 2016.

In this procedure, the surgeon inserts a camera – to see inside – and procedural instruments – to do the work – into the knee via portals on the exterior of the knee. This is commonly referred to as “scoping the knee” and is a relatively non-invasive procedure that can be used for a variety of things. Visual:

I’ve been trying my damnedest to get specific information on the procedure but have been unable to find anything.

Based on his original timeline of 6 weeks – actually turned out to be nearly 10 as he returned Dec 19th – and it being called “minor”, my educated guess is that the procedure was either to remove synovial tissue – lining that surrounds the knee joint – that may have been causing inflammation or to remove damaged articular cartilage.

It honestly doesn’t really matter though because the implication is the same in the risk/reward analysis. Speaking of…

The Risk/Reward Analysis

It’s undeniable that Giles possesses a top flight skill-set, when healthy.

Defensively, he has shown a positional versatility that is so valued in today’s NBA. Lateral quickness, size, and strength that allow him to fit into multiple strategies on PnR while also being able to change shots in the paint and gather rebounds – his block and rebounding rates at Duke are solid.

Offensively, certainly raw, but he possesses a high motor with the ability to attack the offensive glass on the strong or weak-side, be an effective long roll man, and be a rim to rim big with his straight line speed and ability to finish.

The talent is certainly there but there are 2 pertinent question and answers that lie at the crux of his risk/reward ratio:

The questions:

1 – Will he ever get back to his prior level of health?

2 – What’s his risk for re-injury or injury in general?

The answers:

1 – Yes, IF handled correctly.

In reality, it takes about 2 years for an individual to get truly get back from an ACL injury. We know this because it usually around the 2 year mark when there are no discernible side to side testing differences between the two legs –one of the key indicators of injury risk.

That is why I take everything that Giles did or didn’t do at Duke with a giant grain of salt. Not only was he still in the process of recovering from his right ACL surgery but he now had the added variable of an arthroscopy on a previously surgically repaired left knee.

In sum: He is not close to 100% health.

With that in mind, I want to commend Duke’s medical staff, Coach K, and their coaching staff in how they handled him last year. Could he have been pushed more, helped Duke, and possibly guaranteed himself a lottery slot? Sure. But could he have also re-injured himself and become a flyer in the 2nd round or camp invitee or worse? Absolutely.

The fact that he was handled appropriately at Duke and conservatively allowed to enter back into full play is a significant green flag in his long-term recovery.

If you’re drafting him with the understanding that he requires another year or so to be gradually acclimated to the rigors of basketball, then he certainly can return to 100% health.

2 – His injury risk is increased but very difficult to say by how much

The research regarding re-tear rates of the ACL is highly variable but the general consensus is as follows: there’s an increased rate for re-tear, specifically amongst younger athletes. That obviously applies to Harry and all other athletes with an ACL tear as well.

That being said, here’s what concerns me and doesn’t concern me about Giles – remember I told you to keep in mind the nature of his injuries.

On the spectrum of concern, I’m always less worried about direct contact injuries than non-contact injuries because a certain amount of force through a structure is going to cause it to break. As any athlete knows, injury from contact is an inherent risk.

Both of Harry’s ACL injuries were direct contact injuries which tells me the cause is far less likely to be a bio-mechanical issue – for an example of that, watch both of Jabari Parker’s ACL tears which were non-contact, same motion.

What actually concerns me the most – provide that Harry is given sufficient time to recover and acclimate his lower extremities as I mentioned above – is the arthroscopy; not because of the procedure itself but of the implication.

He had surgery on his left knee in June 2013 and a little over three years later he had the arthroscopy on that same knee. This could be hinting at a variety of things:

– some aberrant stress to his knee joint due to the changed mechanics that are inherent after surgery. As one of my professors used to say “no matter the surgery, it’s never the same model.”

– a change in the loading pattern at his knee

– compensation by his left knee for the injured right knee

– it may stem from him playing full bore in 2014 and into 2015 after his left ACL, MCL, and meniscus repair.

I don’t know the answer – obviously! – but the follow-up arthroscopy gives me significant pause in his risk assessment. It makes me wonder if there is a mechanical variable that could result in constant nagging problems.

Now to the question of the hour:

From the Lakers Perspective: If he’s available at 28 and at the top of the remaining draft board, do you draft him?

If the team understands his true recovery timeline and continues to build upon the physical foundation and gradual acclimation process that Duke laid, my answer is:

Yes.

From what I know of Gunnar Peterson’s approach to fitness and development, the front office and coaching staff’s approach to growth and deference to the medical staff’s opinion, ownership’s investment in health and prevention, I think this could be a situation where Harry’s risk is mitigated and eventually allows him to expand his confidence, skills, and minutes – heavily tilting the risk/reward toward the reward.

There’s a risk that he has chronic problems – no denying that- but his potential to impact the game at multiple levels and possibly even develop a mid-range game and be effective on the short roll as he returns to full health and mental confidence is too significant to pass up at the 28th pick.

Thanks for reading and feel free to share, like, and follow the RSS feed! Until next time.